sinus congestion and skin rash

Man, 25, With Sinus Pain, Sore Throat, and Rash | Clinician Reviews

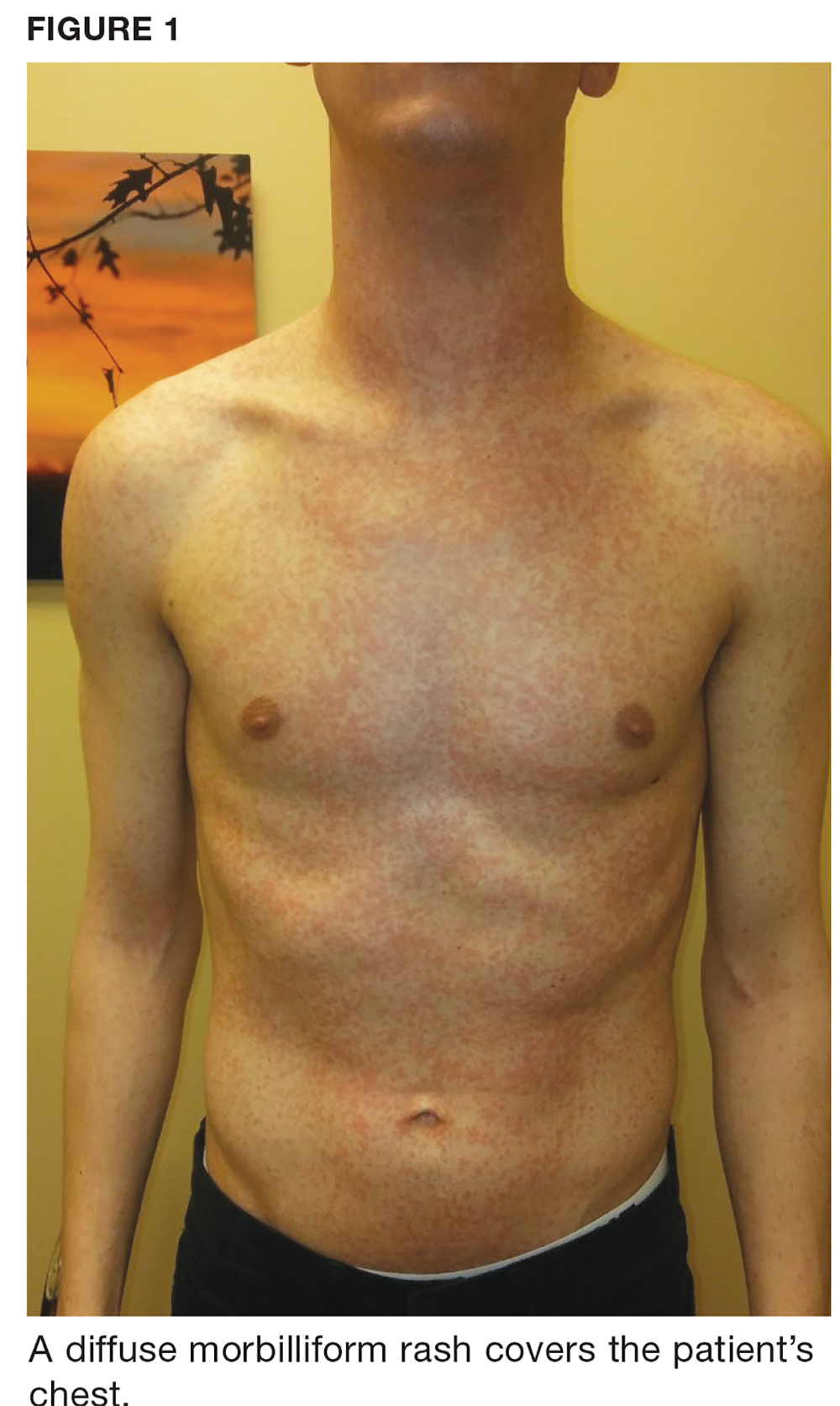

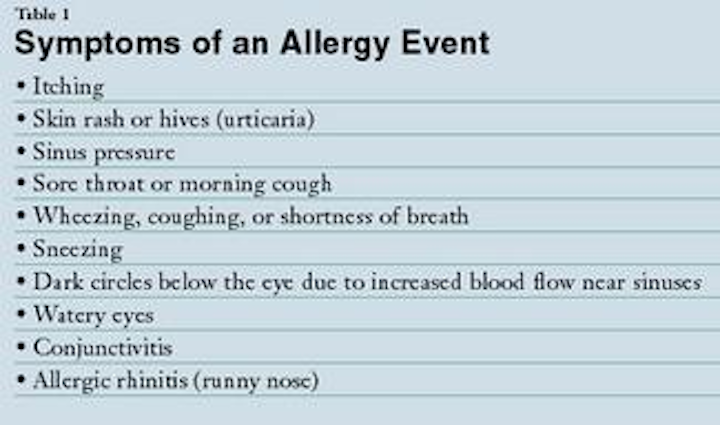

Man, 25, With Sinus Pain, Sore Throat, and Rash | Clinician ReviewsWarning: The NCBI website requires JavaScript to operate. 38-year-old woman with cough and a RashMegan P. Donohue University of the Maryland Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Baltimore, MarylandElizabeth P. Clayborne †University of Maryland School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Baltimore, MarylandZachary D.W. Dezman †University of Maryland School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland Laura J. Bontempo †University of Maryland School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Baltimore, MarylandCASE PRESENTATION (Dr. Donohue)A 38-year-old female presented to the emergency department (ED) with rash, dyspnea, odynophagia and nasal congestion during the previous two weeks. During that time, he sought medical attention twice. The first doctor to evaluate the patient started her on antibiotics for an alleged upper respiratory infection (URI). His symptoms did not improve after completing a 10-day amoxicillin course; then a second doctor prescribed him ciprofloxacin. She was on her eighth day of ciprofloxacin (i.e., 18 full day of treatment) when she introduced our ED with rash and dyspnea. He decided to come to the ED because his cough had gotten worse and had become productive of sputum. He also complained of a month of fevers, chills, night sweats and discomfort. He denied complaints of headaches, chest pain, palpitations, abdominal pain, genitourinary or neurological symptoms. His past medical history was significant for asthma in adults and allergic rhinitis. Medicines included fluticasone, ipratropio, and their recent amoxicillin and ciprofloxacin courses. He had no allergies to known drugs, but he reported gastrointestinal intolerance to fish oil. Her family history was significant for a sister with multiple sclerosis. She was an Iranian immigrant who had moved to Baltimore six months before she presented at our ED. She was married with no children and denied ever using tobacco, alcohol or illicit drugs. In the physical exam, she was alert but seemed uncomfortable as she got into triage that night. She was afebrile (36.7° Celsius) and slightly tachycardia (heart rate of 110 strokes per minute). His blood pressure was 102/68 millimeters of mercury, slightly tachypneic with a respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute, and his oxygen saturation was 97% while breathing air in the room. It was well developed and well nourished, with an estimated body mass index of 22. His head was north-mocephalic and atraumatic. His oropharynx was clear; his neck was flexible and lymphadenopathy was not detected. In the auscultation, he was tachycardia with an S1 and S2, without any murmur, gallop or blond. It was slightly tachypneic without any accessory muscle use, retractions or greater breathing work. He was able to speak in full sentences without difficulty. The patient's lungs were clear for bilaterally unsybilance-free auscultation, rhonchi or measles. His abdomen was soft and non-remaining, and no lower extremity edema was present. I was alert, oriented and adequately interactive. By examining more closely the patient's skin, his rash seemed to have three different morphologies. The first was located on its front and consisted of subcentimeter papulovesicular eruptions with petechiae that were pruristic but not tender (). The second eruption consisted of hemorrhagic vesicles scattered with purpuric macules and was located in its upper and lower distal extremities (). The third rash was an erythematous and indurated plate at the base of the left foot, which was tender and made it painful for her to walk. Papulovesicular eruptions with petechia on the patient's front (fleight). Hemorrhagic vesicles escattered (flecha) with purpuric molecules in the patient's feet. The initial results of the laboratory are shown in –. The patient's electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with normal intervals and without ST or T wave abnormalities. Multi-lobar bilateral infiltrates were revealed in chest X-ray (). A CT scan (CT) of your chest confirmed the presence of bilateral multi-lobar infiltrates and a CT of your breasts showed mucus thickening in everything. An echocardiogram revealed a normal ejection fraction and no valve pathology. They didn't see vegetation. The patient was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation. Then a test was performed that confirmed the diagnosis. Torahx X-ray of a 38-year-old patient with rash and dyspnea, showing multi-lobar bilateral infiltrates (smalls). Table 1 Laboratory results of a 38-year-old patient who has an eruption and dyspnea. ValuesComplete count of blood cells (percentage) of white blood cells (percentage) (percentage) per hemoglobin (percentage) per hematocrite (percentage) per hematocrite (percentage) Table 2 Additional laboratory results of patients 38 years of age who present rash and dyspnea. Additional laboratories Values Screen of the human immunodeficiency virus Rate of sedimentation of ethrocytes (mm/hr)70C-protein reactiva (mg/L)3.3Immunoglobulin E (KU/L)6,266Mm, millimeters; hr, time; mg, milligrams; L, liter; KU, kilounities. Table 3Urinalysis of 38-year-old patient with rash and dyspnea. UrinalysisValuespH7Specific gravity1.003GlucoseNegativeKetonesNegativeProteinNegativeNitrileNegativeLeukocyte esteraseNegative White blood cells Blood cells DISCUSSION TraceCASE (Dr. Clayborne)My approach to cases that contain a lot of non-specific information is to first look at the big picture. I like to identify highlights of the history of the present disease (HPI), past medical history, social history, symptoms review (ROS) and physical examination to isolate what stands out and can give a vision of the difference. The first impressions of HPI were the story of a young woman with a history of asthma and allergic rhinitis, who recently had an ERI that does not respond to two different antibiotics. That patient showed the ED an eruption after taking ciprofloxacin. The first impressions of ROS highlighted that it had a month of constitutional symptoms and fatigue, nasal congestion, sore throat, coughing without hemoptisis and a new eruption with pruritis. The first impressions of social history included his status as an Iranian immigrant who did not drink, smoke or consume drugs. Finally, the first impressions of his physical examination included an afebrile patient, with a stable appearance with tachycardia and tachypnea whose lungs were clear to the auscultation bilaterally, who also had three different morphologies in his face, limbs and sole on one foot. Immediately after my first impressions, the topic I was most concerned about was the rash. I find that many emergency doctors can be uncomfortable with rashes as they often find it difficult to describe correctly, breaking the link between identifying an eruption and making the diagnosis. In this case, the location and characteristics of the eruption were not specific to an etiology with which I was familiar. But I could combine the eruption description with my first impressions to generate a preliminary differential diagnosis. I subdivided my differential diagnosis in the three broad areas: infectious (bacterial, viral or fungal); allergic; and autoimmune. Based on these three categories I started using the data collected in the ED to help reduce my focus. The persistent positives of the laboratory included a mild leucocytosis of 12.1 kilo/microliter with eosinophilia of 10.6%, traced blood orinalisis, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 70 millimeters per hour, a C reactive protein of 3.3 milligrams per litre, and its screen for the acquired human immunodeficiency virus was non-reactive. These are the laboratories that I would expect to result during the patient's visit to ED. In the ED I you would also see your chest X-ray and CT chest showing multiple bilateral infiltrates. With this information, if I were the treatment doctor, I would ask for antibiotics and admit the patient for an outpatient job. The results most likely to be done during the patient stay showed sinusitis, a normal heart ejection fraction and a high immunoglobulin E (IgE) of 6,266 kilounities per litre. Based on these additional data, I returned to my comprehensive differential diagnosis to see what fits and didn't fit into each category. Allergic etiologies would include an eruption, respiratory symptoms and perhaps a slight elevation of inflammatory markers, but do not explain the constitutional symptoms or positive findings in X-ray and CT. Autoimmune etiologies would explain the constitutional symptoms, eruption and infiltration, but would question why only a few of the inflammatory markers were elevated. Infectious etiologies, especially fungal infections, could account for constitutional symptoms, lung disease, eosinophilia and elevated IgE. My first two diagnostics based on the patient's presentation along with their laboratory results are eosinophilic granulomatose polyangitis (EGPA), also known as Churg-Strauss syndrome, and aspergillosis. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis begins when the patient is colonized by inhaling fungal spores. Patient symptoms are often constitutional (weakness, fatigue, and low-grade fevers) and not specific (lack of breath and cough that is productive but does not respond to antibiotics). Patients often present hemoptissis, which did not occur in this case. The infection can spread from the respiratory tree below several organs, most of the time the brain. These patients will develop abnormalities in CT (infarts, lesions that increase the ring, bleeding, abscess) and will begin to suffer from seizures. Patients with aspergillosis will often present with eosinophilia, elevated levels of IgE, abnormal chest and CT X-rays, sinusitis and a characteristic eruption. Eruption begins as indurated papules or plates, solitary or multiple erythematous or raped. It can be tender and quickly evolve into pustules, hemorrhagic vesicles, or scaras. However, this patient does not have any of the risk factors for aspergillosis (prolonged extremity, transplant [especially lung], prolonged high-dose corticosteroid therapy, hematological malignity, cytotoxic therapy, or advanced acquired immunologic deficiency syndrome. This patient has sinusitis and not hemoptissis, both incompatible with aspergillosis. The EGPA was first described in 1951 by Churg and Strauss. He described a syndrome in 13 patients who had asthma, eosinophilia, granulomatous inflammation, necrotizing systemic vasculitis and necrotizing glomerulonephritis. In 1990 the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) proposed the following six criteria for the diagnosis of GPA:Asthma (wheezing, expiratory rhonchi)Eosinophilia of more than 10% in peripheral blood Paranasal sinusitis Pulmonary infiltration (can be transient) Histological test of vasculitis with extravascular eosinophilic epithesis If I were the treatment doctor, I would treat empirically with antifungals due to concern about aspergillosis. However, for this case exercise, I think a biopsy would confirm a diagnosis of EGPA. CASE OUTCOME (Dr. Donohue) The diagnostic study performed was a stroke biopsy of a hemorrhagic gallbladder on the right foot. He highlighted two key conclusions: 1) eosinophils that surround a central granuloma; and 2) the cross section of a blood vessel with central necrosis. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of EGPA, also known as Churg-Strauss syndrome. Our patient was admitted to an outpatient medical service, but the diagnostic biopsy was performed at the DD before admission. During the hospitalization service, many consultants participated in their care, including dermatology, rheumatology, pulmonology and infectious diseases. Bronchoscopy, bronco-alveolar washing and pulmonary biopsy were subjected to bronchoscopy. Ultimately, based on the criteria of ACR EGPA, she was diagnosed with EGPA and began in high-dose prednisone 60 milligrams (mg) daily. In outpatient follow-up, he transferred to azotyoprine and a year of follow-up was doing well. DISCUSSION DISCURSE is a rare vasculitis with an estimated incidence of one to three cases per million people. In the early history of its recognition, there was no reliable data on the incidence due to its similarities with other heterogeneous disease processes and the lack of diagnostic criteria. EGPA was first described in 1951 by two young pathologists from New York City who were studying vasculitis. As pathologists, their case study data were obtained from autopsies in which they recognized "the appearance of a clinical syndrome of severe asthma, fever, and hypereosinophilia." Note, this was in addition to the fact that these patients had already known vasculitis and had already died. However, it was "the discovery of granulomatous lesions, both inside the walls of the vessels and in the connective tissue" which made it different from other allergic and vasculitid syndromes. Churg and Strauss theorized that 11 of the 13 cases of sentinel had died because of this syndrome to which they applied their eponym. Since 1951, the underlying pathology and pathogenesis of the EGPA has become better understood. As a result, the name was changed from Churg-Strauss syndrome to EGPA, which best describes the underlying disease process and the phases of its clinical manifestations. EGPA has three different clinical phases. The first, or prodermal, is characterized by the beginning of asthma in the second or third decade of life. It is often associated with allergic rhinitis and recurrent sinusitis. The second phase, eosinophilic, is marked by peripheral eosinophilia with organ infiltration. Peripheral eosinophilia can be masked by steroid therapy. The infiltration of eosinophilic organs occurs more commonly in the lungs, peripheral nerves and skin, but it can occur in any organ system, creating a series of clinical presentations. This stage of the disease is difficult to distinguish from other hypereoinophilic conditions. The third phase of the EGPA is vasculítica; this phase, unique in the EGPA, makes it fatal if not treated. Patients with pulmonary GPA may develop lung infarction, nodules or diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. The most common findings of the CT include bilateral opacities of ground glass, air space consolidation, centrilobular nodules and thickening of the bronchial wall., Heart infiltration can cause heart infarction, pericarditis or congestive heart failure. The intervention of the central nervous system can lead to neuropathy, mononeuritis, seizure, stroke or coma. One study found that mononeuritis was the second most common presentation of EGPA, second only to asthma. In the EPGA gastrointestinal system, it can cause colecistitis, pancreatitis, or gastroenteritis. Vascultic involvement of the kidney system can result in proteinuria, hematuria, glomerulonephritis or kidney failure. Any of these complications can be the presentation of symptoms of a patient; the case we have highlighted is the most common presentation of EGPA. Participation of the organ system is important because of its prognostic value calculated by the score of five factors. If two or more of the following organ systems are involved, heart system, gastrointestinal, nervous or kidney, five-year mortality is 50% untreated. Diagnostic criteria have changed over time. Churg and Strauss initially described a disease that was diagnosed only in the biopsy. An emphasis on biopsy and pathological findings was considered to lead to the disease being diagnosed. The RTA revised the diagnostic criteria in 1990 to include more common features: the presence of asthma; eosinophilia √0% in the differential white blood cell count; mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy; non-fixed lung infiltrates in the image; parasinuating abnormality; or a characteristic biopsy. If four or more criteria were present, the sensitivity was 85% and the specificity of 99.7%. Alternatively, if a patient had asthma, eosinophilia and history of allergy or drug sensitivity, the sensitivity was 95% and the specificity of 99.2%. Now that the biopsy is no longer necessary to confirm the diagnosis, a provider's clinical suspicion index has a significant impact on the recognition and diagnosis of EGPA. It has been suggested that anti-leukotriene drugs can play a role in the development of EGPA, but this is controversial.– The current understanding is that the prolonged survival of eosinophiles due to the inhibition of apoptosis mediated by CD95 plays a role in the pathogenesis of EGPA. Recent data suggest that the release of T lymphocyte cytokines can be an important step. Although the exact cause of EGPA has not yet been fully clarified, treatment guidelines are available. High-dose glucocorticoids (1mg/kg/day prednisone) for at least two or three weeks is the cornerstone for treatment to obtain remission. EGPA responds well to first-line treatments, but it has been shown that relapse occurs in up to 25% of patients. Cytophosphamide is the main pharmacotherapy for the induction of remission. Azothioprine and metotrexate are used for maintenance therapy for patients with the involvement of life-threatening or organ diseases. Intravenous immunoglobulin is considered second-line treatment for refractory disease. The new treatment modalities under consideration include the exchange of plasma and the use of monoclonal antibodies. EGPA treatment should always include a multidisciplinary team, including rheumatology. DIAGNOSISEosinophilic polyangitis granulomatosa, also known as Churg-Strauss POINTSEGPA syndrome of TECHNOLOGY is a rare but deadly vasculitis. The typical characteristics of EGPA are asthma with allergic rhinitis and recurrent sinusitis, peripheral eosinophilia and vasculitis. High clinical suspicion is paramount as it is a clinical diagnosis. Differential diagnosis should be expanded when a patient has gone back and has already failed initial medical therapy. Diagnostic impulse in the DHD can play a key role in performing the correct diagnosis. FootnotesSection Editor: Rick A. McPheeters, The full text available has been obtained and presented through open access in the informed consent of the documented patient and/or approval of the Institutional Review Board for the publication of the present report. Interest Conflicts: Under the CPC-EM article submission agreement, all authors must disclose all affiliations, sources of finance and financial or management relationships that may be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors revealed nothing. REFERENCESFormats: Share , 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD, 20894 USA

Common Types of Allergies - Fort Worth ENT & Sinus

Man, 25, With Sinus Pain, Sore Throat, and Rash | Clinician Reviews

Can pollen cause a hay fever rash? Symptoms and remedies

Cough and Rash: Causes, Photos, and Treatments

Can pollen cause a hay fever rash? Symptoms and remedies

Skin Allergy Specialist in Delhi|Allergy Treatment | DermaWorld Skin Clinic

18 Symptoms of Sinus Infection (Sinusitis), Treatment, Causes & Complications

Cough and Rash: Causes, Photos, and Treatments

Symptoms Of Allergies Skin Rash, Allergic Skin Itching, Tearing From The Eyes, Cough, Sneezing, Runny Nose, Headache Stock Vector - Illustration of allergy, rash: 175028947

New Rash and Fever in a Woman With Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Gastroenterology

/does-singulair-differ-from-antihistamine-for-allergies-82878-5c77344c46e0fb00019b8d33.png)

Should You Use Singulair for Allergies?

7 Sneaky Signs Your Allergy Medicine Isn't Working | The Healthy

Rash around eyes: Causes, symptoms, and treatment

Man, 25, With Sinus Pain, Sore Throat, and Rash | Clinician Reviews

Cough and Rash: Causes, Photos, and Treatments

Allergy - Wikipedia

Relief for Out-of-Control Allergy Symptoms

Can you be allergic to Allergy Medications (Antihistamines) | APAA

Visual Guide To Sinusitis

Itching: Pictures, Causes, Diagnosis, Home Remedies & More

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/could-i-have-a-marijuana-allergy-1132480-4d1485b2acc04452ad0816621a311340.jpg)

Weed Allergy Symptoms and Treatment

Can pollen cause a hay fever rash? Symptoms and remedies

skin allergies, legs women. - Gupta Allergy | Allergy & Asthma Specialists

Is Itchy Skin a Sign of Seasonal Allergies? | Windsor Dermatology

404 Page | Homeopathy for allergies, Watery eyes, Sinus remedies

Itching: Pictures, Causes, Diagnosis, Home Remedies & More

Skin Rashes in Children: Symptoms, Causes & Treatment

Beyond the eczema rash | National Eczema Association

How Do You Get Rid of an Allergic Reaction Rash? - Oak Brook Allergists

Ah-Choo!!!Allergies: The Good, The Bad and The Sneezy | Registered Dental Hygienist (RDH) Magazine

What is an allergy sensitizer, and how does a chemical become one?

Could that rash be from wheat? | Autoimmune skin, Integumentary system, Canker sore

Why Are My Allergies Worse Indoors? Symptoms, Treatment & Test Kits

A Guide to Cannabis Allergies and Symptoms | Leafly

A Complete Guide to Allergies | Allergy & Asthma Network

Allergies vs. Sinus Infections | California Head & Neck Specialists

Is jewelry causing that skin rash? | Ohio State Medical Center

Test Your Skin Allergy Smarts

Hammerling: Skin rash could be a sign of COVID-19 infection

Managing Seasonal and Year-Round Allergies: Discovering an Alternative Approach | Baton Rouge Parents Magazine

Posting Komentar untuk "sinus congestion and skin rash"